Latest News

My latest ramblings.

Enjoy! I definitely got important things to say

My latest ramblings.

Enjoy! I definitely got important things to say

In an age of noise, confusion, and infinite scrolling, there’s something about Alan Watts that stops you mid-scroll. His voice—part lullaby, part lightning bolt—feels like a long-lost friend whispering through your soul. His words don’t just inform; they disarm. They don’t tell you how to live—they make you feel alive.

To understand Alan Watts is not merely to study a man. It is to wander into a mirror and see the shape of your own existence ripple into new, playful dimensions. He wasn’t a guru, though many tried to crown him as such. He wasn’t a monk, though he walked in reverence. He wasn’t a saint, though his words calmed saints and sinners alike. Alan Watts was, in the truest sense, a performer of truth—a cosmic bard spinning silk from paradox.

Born in 1915 in Chislehurst, a quiet suburb in England, Alan was never the boy to settle for simple answers. His mother was religious, his father rational. Somewhere between the two, Alan carved a path through paradox. By his teens, he was deep into Eastern philosophy. Zen, Taoism, Vedanta—all filtered through the lens of a young boy who wasn’t trying to escape life but understand it.

He emigrated to the United States in his twenties and briefly served as an Episcopal priest. But Alan’s spirit wasn’t built for pulpits and stained glass. He wanted the sky open, the mind expanded. So he left the church—politely, respectfully, but completely—and plunged into the waters of comparative philosophy.

Watts was drawn to the idea that truth wasn’t something you possessed. It was something you danced with. In Zen, he found a sense of play. In Taoism, a gentle flowing. In Vedanta, a blurring of boundaries. In every tradition, he unearthed a recurring echo: that the self is not a separate entity but a wave of the vast ocean of life.

By the 1950s and ’60s, America was cracking open. The rigidity of post-war life gave way to psychedelics, Eastern spirituality, and a hunger for meaning beyond materialism. Alan Watts became a voice—not just for the counterculture, but for the inner culture of millions.

He lectured in smoky halls, under redwoods, beside crackling fires. He recorded hundreds of talks—on radio, cassette, and in the hearts of listeners. His voice became a sort of medicine for modern madness.

One of his most famous teachings was the illusion of the separate ego. According to Watts, we’ve been tricked into thinking we are isolated selves living in a universe that is other. But in truth, we are the universe—looking back at itself through human eyes. Just as an apple tree “apples,” the universe “peoples.”

This wasn’t some poetic metaphor for Watts. It was a lived reality. If you listened closely, you could hear the cosmic giggle behind every word he said.

Watts’ genius lay not in explaining complexity, but in exploding it. He used paradox not to confuse, but to liberate. He would say things like:

“Trying to define yourself is like trying to bite your own teeth.”

“Muddy water is best cleared by leaving it alone.”

“The menu is not the meal.”

These weren’t riddles. They were keys—unlocking the mental cages we didn’t even know we lived in. He invited people to let go of control, to trust the flow of life, to understand that letting go isn’t a defeat, but the beginning of real freedom.

He often quoted the Tao Te Ching, savoring its quiet wisdom:

“The way that can be spoken is not the eternal Way.”

Watts knew that some truths were too vast for language—and that was okay. The point wasn’t to define life, but to live it.

But let’s not canonize him too quickly. Alan Watts was no ascetic. He loved wine, laughter, and good conversation. He had affairs. He was married multiple times. He struggled with his responsibilities, with his addictions, with the very human mess of being human.

And yet, perhaps that is what made him all the more compelling. He didn’t speak from a mountain top. He spoke from the middle of the dance floor. He didn’t claim purity. He claimed presence. He was not without contradiction—he was contradiction, incarnate, and he made peace with that.

For Watts, the point was never perfection. It was awareness. To be fully present in the moment, whether that moment was beautiful, broken, or both.

At the age of 58, Alan Watts died in 1973 . Some say it was too soon. But maybe Watts himself would have disagreed. After all, he often spoke of death as not the end. But the return. Like the crest of a wave returning to the ocean.

Decades later, his voice continues to ripple across podcasts, YouTube videos, and meditation apps. Never Young people who saw a world without Wi-Fi now listen to this British philosopher in the quiet of their earbuds. Why?

Because even in this hyper-digital age, Watts touches something timeless. So he reminds us of what we forget:

Here Perhaps Watts’ greatest gift wasn’t his knowledge. But his invitation. Then he didn’t want you to believe in him. So he wanted you to believe in being. To trust that the rhythm of the universe is already within you. That you don’t need to climb toward enlightenment. Only you need remember what you already are.

“You are the big bang, the original force of the universe, coming on as whoever you are.”

What a radical, liberating idea.

To be alive is not to chase purpose like a carrot on a stick. To be alive is to wake up now. To hear a bird sing and know that it, too, is the voice of God. To laugh, not because life is easy, but because it is so beautifully absurd.

That was Alan Watts’ religion—not a set of rules, but a way of seeing. A way of being. And in a world that often asks us to shrink, conform, or perform, Watts asked something more daring:

Be the whole damn universe, dancing in a body that breathes.

And maybe—just maybe—that’s all the meaning we ever needed.

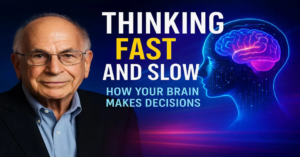

“Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.” — Daniel Kahneman

When psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman passed away in March 2024, he left behind a monumental legacy: a radical understanding of how human minds actually work. His 2011 masterpiece, Thinking, Fast and Slow, isn’t just a psychology book—it’s an operating manual for the human brain. Through decades of research, often with collaborator Amos Tversky, Kahneman dismantled the myth of human rationality and revealed a mind governed by two competing systems: one intuitive, the other analytical. This book has sold over 2.6 million copies and fundamentally reshaped fields from economics to medicine, yet its true power lies in how it transforms everyday decision-making.

Speed and Nature: Operates automatically, intuitively, and effortlessly. When you jerk your hand from a hot stove, recognize anger in a facial expression, or complete the phrase “war and ____,” you’re using System 1. It handles approximately 95% of our daily decisions.

Evolutionary Role: Designed for survival. It detects threats (a slithering shape in the grass) and patterns (a child’s cry of pain) instantly. However, it’s prone to cognitive biases—jumping to conclusions based on limited information.

The WYSIATI Trap: “What You See Is All There Is” (WYSIATI) is System 1’s tendency to construct coherent stories from whatever information is available, ignoring critical gaps.

Example: Hearing “a shy, helpful man with a need for order,” most people guess “librarian” despite there being 20x more farmers—statistics fade before vivid stereotypes.

Effort and Logic: Engages in slow, effortful reasoning. Calculating 17×24, comparing insurance policies, or parking in a tight space requires System 2. It’s logical but lazy; it prefers endorsing System 1’s intuitions unless forced to intervene.

Cognitive Strain: When tired or overwhelmed, System 2 disengages. A study showed judges granting parole more often after lunch—depleted energy reduced their capacity for complex deliberation.

The Tug-of-War: Systems constantly interact. Driving a familiar route (System 1) shifts to System 2 when fog obscures the road. But System 2’s laziness creates vulnerability:

ease over truth. A statement in bold font feels truer than the same in light font simply because it’s easier to read.

Kahneman exposed systematic errors (“biases“) hardwired into human cognition:

Effect: Initial numbers disproportionately sway decisions. In one experiment, subjects spun a wheel rigged to land on 10 or 65, then estimated African nations in the UN. Those seeing “10” guessed 25%; those seeing “65” guessed 45%.

Real-World Impact: Car dealers list high “sticker prices” to anchor negotiations. Salary offers set at $70,000 make $65,000 seem reasonable—even if the role’s market value is $60,000.

Heuristic: We judge likelihood by how easily examples come to mind. After a plane crash, people overestimate aviation risks; vivid media coverage amplifies this.

Terrorism vs. Diabetes: Though diabetes kills 200x more Americans than terrorism, fear resources skew toward the latter. Why? Vivid imagery trumps statistics.

Core Principle: Losing $100 hurts 2.5x more than gaining $100 pleases. This asymmetry shapes decisions:

Investing: People hold plummeting stocks to avoid “realizing” losses.

Sports: Golfers putt more accurately for par (avoiding bogey) than for birdie—fear drives precision.

Framing Effect: Surgery with a “90% survival rate” sees higher uptake than one with a “10% mortality rate“—identical outcomes, opposite reactions.

Definition: Underestimating time, costs, and risks. Kitchen remodels planned for $18,658 balloon to $38,769 on average; 90% of drivers believe they’re “above average“.

Root Cause: System 1’s focus on ideal scenarios (“inside view“) while ignoring base rates (“outside view“). Sydney’s Opera House finished 10 years late and 1,400% over budget.

Valid Intuition: Chess masters instantly spot winning moves after 10,000+ hours of pattern recognition. In stable environments (firefighting, nursing), trained intuition excels.

Danger Zones: In unpredictable realms (stock markets, politics), experts often underperform algorithms. Psychologist Philip Tetlock found pundits’ predictions worse than chance.

Solution: Replace intuition with simple algorithms. A study showed formulas outperforming clinical judgments in diagnosing heart attacks. When stakes are high, objectivity beats “gut feel”.

Experiencing Self: Lives in the present—the pain of a headache, the joy of sunshine.

Remembering Self: Constructs narratives prioritizing peaks and endings. Example: A colonoscopy’s prolonged mild discomfort is remembered as less painful than a shorter but sharper one if it ends gently.

Implication: We sacrifice happiness (e.g., working a hated job for years) to serve the remembering self’s desire for a “meaningful story.” Recognizing this split helps align decisions with actual well-being.

Some priming studies cited (e.g., “Florida effect” linking elderly words to slower walking) faced scrutiny during psychology’s replication crisis. Critics argue effects are smaller than initially claimed.

The “two systems” model is debated as overly simplistic. Neuroscientists note brain functions are distributed, not binary—yet the framework remains invaluable for explaining behavioral patterns.

Unlike abstract theories, Kahneman’s insights are actionable:

“The illusion that we understand the past fosters overconfidence in our ability to predict the future.” — Kahneman

His greatest gift was humility. By mapping our cognitive flaws, he freed us from the delusion of perfect rationality. In a world demanding ever-faster decisions, Thinking, Fast and Slow remains a vital call to sometimes—critically—slow down.

Kahneman’s work underpins “nudge units” in governments worldwide and behavioral finance. His book isn’t just about thinking—it’s about relearning how to be human in an irrational world.

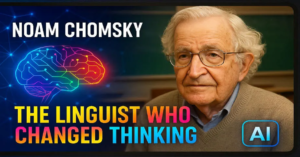

For over seven decades, Noam Chomsky has been a tectonic force in multiple intellectual domains. So reshaping linguistics, igniting the cognitive revolution. Then providing a relentless critique of power structures. His journey from a Philadelphia bookstore to MIT lecture halls and global protest movements reveals a mind. So uniquely equipped to decode both the hidden structures of language and the visible machinery of oppression.

Here was born Avram Noam Chomsky on December 7, 1928, in Philadelphia. So Chomsky’s worldview was forged in the crucible of social struggle. His early memories included “security officers beat\[ing] women strikers outside a textile plant“. During the Great Depression—a scene that imprinted on him the violence underpinning authority. By age 10, he was writing editorials about the Spanish Civil War. Displaying a precocious grasp of global politics.

Intellectuality of Chomsky’s awakening crystallised in New York’s anarchist bookshops. His uncle’s 72nd Street newsstand. Where working-class intellectuals debated politics and philosophy. Here, he absorbed libertarian socialist principles. Then that would define his politics: the belief that all people could comprehend complex issues and that illegitimate authority must be challenged.

At 16, he entered the University of Pennsylvania. But nearly abandoned academia until meeting Zellig Harris, the father of structural linguistics. Under Harris’s mentorship, Chomsky’s linguistic genius ignite. Later, radically, though he would transcend his teacher’s ideas.

In 1959, Chomsky detonated a 40-page critique of B.F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior that permanently altered psychology. Skinner argued language was conditioned response—children learned words through rewards/punishments (e.g., saying “candy” to receive sweets). Chomsky countered with two devastating insights:

This wasn’t just linguistics—it was a manifesto for mentalism. Chomsky argued that studying external behavior alone was like diagnosing a broken clock by only observing its hands; true understanding required examining internal mechanisms.

Chomsky’s magnum opus, Syntactic Structures (1957), introduced transformational grammar—a computational system where a finite set of rules generates infinite sentences. At its core lay three radical claims:

“A plausible theory has to account for the variety of languages […] yet be simple enough to explain how language emerged quickly through some small mutation.” — Chomsky

Chomsky’s political activism erupted during the Vietnam War. His 1967 essay “The Responsibility of Intellectuals” indicted academia for complicity in state violence, arguing that intellectuals’ privilege demanded greater moral accountability. This launched a parallel career analyzing:

Despite arrests and placement on Nixon’s “enemies list”, Chomsky never wavered. His 2002 critique of the War on Terror (9-11: Was There an Alternative?) labeled the U.S. “a leading terrorist state”—a provocation that made it a surprise bestseller.

Chomsky’s magnum opus, Syntactic Structures (1957), introduced transformational grammar—a computational system where a finite set of rules generates infinite sentences. At its core lay three radical claims:

“A plausible theory has to account for the variety of languages […] yet be simple enough to explain how language emerged quickly through some small mutation.” — Chomsky

Chomsky’s linguistic theories evolved dramatically, confounding supporters and critics alike:

| Phase | Key Idea | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Theory (1960s) | Deep vs. Surface Structure | “John is easy to please” vs. “John is eager to please” |

| Principles & Parameters (1980s) | Innate switches for grammar variations | Pro-drop parameter (Spanish permits omitted pronouns) |

| Minimalism (1990s–present) | Language as optimal computational system | Only recursion + interface mappings to thought/sound |

By 2002, Chomsky and colleagues pared UG to near-minimal components: recursion (embedding phrases) and mappings to sensory/motor systems. This retreat from “rich UG” shocked followers—suddenly, categories like “verb” or “tense” were emergent properties, not innate modules. Critics like Daniel Everett used the Pirahã language (allegedly lacking recursion) to challenge even this lean framework, though Chomsky dismissed it as flawed analysis.

Chomsky’s absolutist stance on free speech led him to defend Holocaust denier Robert Faurisson’s right to publish (not his views). The backlash, especially in France, showcased his consistency—even when defending “unpopular” speech.

Chomsky occasionally drew questionable scientific analogies, like comparing UG to a hypothetical “universal genome” for multicellular life—a fringe theory biologists dismissed. His claim that “culture influences language” is “almost meaningless” (defining culture as “everything that goes on”) frustrated anthropologists.

Some Christians embraced UG as evidence of God-given language capacity, while others rejected its naturalism. Missionary-linguists noted its practical value for Bible translation despite theoretical disagreements.

At 96, post-stroke yet intellectually undimmed, Chomsky’s legacy is multifaceted:

As he once reflected: “I’ve done something decent with my life”. Few thinkers have so thoroughly reshaped our understanding—both of the sentences we speak and the systems that silence us.

“Two questions for humanity: How does your language work? And why is your world arranged as it is? Chomsky gave us tools to dismantle both.” — Adapted from Neil Smith

For over two decades, Brene Brown has revolutionized our understanding of human connection by studying what most of us desperately avoid: shame, vulnerability, and the terrifying uncertainty of being truly seen. What began as a quest to understand connection evolved into a seismic shift in psychology, leadership, parenting, and personal growth. Her message is deceptively simple yet profoundly challenging: Vulnerability is not weakness; it is the birthplace of courage, creativity, and belonging.

🔴 1. The Radical Courage of Showing Up: Brené Brown and the Transformative Power of Vulnerability

🔵 2. The Accidental Discovery: From Shame to Wholeheartedness

🔵 3. The Wholehearted Revolution

└── 🔵 3.1. Table: Brené Brown’s Wholehearted Living Framework

🟢 4. The Physics of Vulnerability: Why It’s So Hard

🟢 5. The Vulnerability Toolkit: Beyond Theory into Practice

├── 🟢 5.1. Disarm Shame with Storytelling

├── 🟢 5.2. Set Boundaries for Emotional Safety

├── 🟢 5.3. Rewrite Your “Armory” Narratives

└── 🟢 5.4. Table: Vulnerability Armor vs. Wholehearted Practices

🌸 6. The Cultural Earthquake: Parenting, Leadership, and Creativity

├── 🌸 6.1. Revolutionary Parenting

├── 🌸 6.2. Daring Leadership

└── 🌸 6.3. The Creative Imperative

🔵 7. The Arena: Where Vulnerability Meets Courage

🟢 8. The Unending Practice: Why Vulnerability Demands Courage

🌸 9. The Invitation: Your Wholehearted Rebellion

🔵 10. Further Exploration

Dr.Brown’s journey started conventionally enough. As a qualitative researcher and self-proclaimed “recovering perfectionist,” she aimed to study human connection. But her participants’ stories took an unexpected turn:

“When you ask people about love, they tell you about heartbreak. When you ask about belonging, they tell you about excruciating exclusion… Six weeks into research, I hit this unnamed thing that unraveled connection.”

That “unnamed thing” was shame—the pervasive fear that something about us makes us unworthy of love and belonging. For six years, Brown meticulously analyzed thousands of stories, coding over 11,000 incidents from 1,280 interviews and 3,500 journal entries. Her findings revealed shame’s universality but also pointed to a surprising antidote: vulnerability.

Frustrated by shame’s grip, Brown pivoted her research. Using what she calls “indirect measurement” (borrowed from chemistry), she studied people who lived with resilience despite shame. She labeled them the “Wholehearted”. These individuals shared ten key traits, including:

| Core Practice | What It Replaces | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Authenticity | People-pleasing | Deeper relationships |

| Self-Compassion | Perfectionism | Resilience to shame |

| Embracing Vulnerability | Emotional Armor | Innovation and courage |

| Gratitude and Joy | Scarcity Mindset | Emotional abundance |

Vulnerability, Brown argues, follows emotional “laws of physics”:

Brown’s personal confrontation with these truths was brutal. After her 2010 TEDxHouston talk—now viewed over 60 million times—she woke with “the worst vulnerability hangover of [her] life.” Her academic training clashed violently with her findings: “My mission to control and predict had turned up the answer that the way to live is with vulnerability and to stop controlling”. This sparked a year-long “street fight” with her own resistance, culminating in what her therapist called a “spiritual awakening.”

Brown’s genius lies in translating research into actionable strategies:

Shame thrives in silence. Brown encourages “story stewardship”: sharing shame experiences with empathetic listeners. Neuroeconomist Paul Zak’s research confirms this—stories trigger cortisol and oxytocin, enabling connection and healing.

Vulnerability isn’t indiscriminate exposure. Brown’s BRAVING framework (Boundaries, Reliability, Accountability, Vault, Integrity, Non-judgment, Generosity) creates containers for trust.

Perfectionism, numbing, and foreboding joy are armor against vulnerability. Brown teaches:

| Armor | Wholehearted Alternative | Daily Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Perfectionism | Self-Compassion | “I embrace my humanity” |

| Numbing (busyness/substances) | Mindfulness | 5-minute breath checks |

| Foreboding Joy | Gratitude Journaling | 3 daily joy acknowledgments |

Brown’s work transcends self-help, challenging systemic norms:

“Our job isn’t to say, ‘Look at her, she’s perfect. Keep her perfect…’ It’s to say, ‘You’re imperfect, wired for struggle, but worthy of love.’”

Brown condemns “perfect parenting,” urging instead for modeling vulnerability: apologizing, setting boundaries, and celebrating effort over outcomes.

In Dare to Lead, Brown argues vulnerability drives innovation: “No vulnerability, no creativity. No tolerance for failure, no innovation”. Leaders must:

Vulnerability is non-negotiable for artists: “To create is to make something that never existed before. There’s nothing more vulnerable”. Brown’s research shows creativity requires releasing comparison and “hustling for worthiness”.

Brown often quotes Theodore Roosevelt’s “Man in the Arena” speech:

“The credit belongs to those… whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood… who fails while daring greatly”

Her “arena” metaphor reveals three truths:

Living vulnerably isn’t a one-time choice. Brown’s research shows it’s a daily practice of “courage over comfort”:

As Brown told Krista Tippett:

“The most beautiful things I look back on are coming out from underneath things I didn’t know I could get out from underneath. The moments that made me were moments of struggle”

Brown’s legacy isn’t just research—it’s a call to rebel against a culture of scarcity and armor:

In a world demanding invulnerability, choosing tenderness is revolutionary. As Brown sings along to David Gray’s My Oh My: “What on earth is going on in my head? You know I used to be so sure…” . The surrender of false certainty, she shows, is where true courage begins.

At the heart of Jordan Peterson philosophical system lies a binary as ancient as mythology itself: Order and Chaos—the twin pillars of human existence. Order represents the known, the structured, and the predictable: your morning routine, societal laws, and the comfort of tradition. Its shadow side manifests as stagnation, tyranny, and the suffocation of creativity. Conversely, Chaos embodies the unknown, the formless potential of existence: the unexpected job loss, the creative breakthrough, and the shattering of worldview after tragedy. Yet within its depths lie both creative rebirth and annihilating terror.

Peterson crystallises this duality through evolutionary biology and mythological analysis. Our ancestors, he argues, encoded this understanding in creation myths worldwide—particularly in the Genesis narrative where God’s Word (Logos) imposes order on primordial chaos. This isn’t mere superstition but a profound mapping of psychic reality: consciousness itself emerges when we impose conceptual order on chaotic sensory input.

| Order | Chaos |

|---|---|

| Explored territory | Unexplored territory |

| Predictability | Uncertainty |

| Structure & tradition | Creativity & possibility |

| Tyranny/stagnation (shadow) | Annihilation/terror (shadow) |

Human flourishing occurs not in order or chaos alone but in the dynamic tension between them. Peterson illustrates this through clinical experience: patients trapped in excessive order suffer debilitating rigidity, while those drowning in chaos experience paralyzing overwhelm. The optimal path resembles a “tightrope walk”—maintaining enough structure for stability while embracing sufficient uncertainty for growth.

This balance manifests practically through Peterson’s now-famous rules:

The neuropsychological foundation reveals why this works: our brains process novel stimuli (chaos) through the amygdala-driven threat response, while familiar patterns (order) activate reward pathways. Meaning emerges when we consciously mediate between these systems—a concept Peterson expands in Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life, written during his wife’s cancer battle and his own benzodiazepine dependence crisis. His personal descent into chaos—Russian rehab clinics, induced comas—became the crucible for rules like “Be grateful in spite of your suffering”.

Peterson’s analysis extends beyond the individual to civilization’s architecture. Societies thrive when balancing structured institutions (order) with individual sovereignty (chaos-introducing innovation). He identifies two catastrophic imbalances:

The antidote? Classical liberalism—not as mere politics but as a psychological framework honoring the “sovereign individual” who revitalises decaying structures. Peterson traces this to Judeo-Christian foundations: the individual as divinely imbued with the responsibility to “subdue chaos” through truthful speech and ethical action. When institutions suppress these individuals—as when the Ontario College of Psychologists threatened Peterson’s license for climate change skepticism—they commit what he calls a “spiritual crime” against society’s regenerative capacity.

Peterson’s most revolutionary contribution lies in framing personal crisis as an alchemical vessel. Chaos isn’t merely to be feared; it’s the essential ingredient for rebirth. Clinical examples abound:

The mechanism for this transformation is truthful articulation—”making order from chaos through specific speech.” When patients precisely name their suffering (“My marriage feels like imprisonment”), vague dread crystallises into addressable reality. This mirrors Genesis’ Logos—divine speech imposing order on void.

| Stage | Psychological Process | Practical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chaos | Crisis/disintegration | Job loss, illness, betrayal |

| Confrontation | Truthful articulation of reality | Journaling, therapy, honest conversation |

| Ordering | Implementing new structure | New routines, boundaries, goals |

| Integration | Renewed meaning/perspective | Wisdom, resilience, purpose |

Peterson’s own life demonstrates this: his 2016 clash over compelled speech legislation (Chaos) birthed a global movement (New Order). His near-death experiences during illness forged Beyond Order‘s emphasis on gratitude amid suffering.

Peterson’s framework illuminates contemporary conflicts with startling clarity:

Ultimately, Peterson’s philosophy culminates in a deceptively simple prescription: Assume maximum responsibility. His clinical data reveals astonishing correlations—individuals embracing burdens (aging parents, challenging careers) often report increased life meaning despite objective hardship. Why? Responsibility forces engagement with chaos’s productive edge.

Practical implementation occurs through:

Jordan Peterson’s exploration of Order and Chaos resonates because it mirrors our lived reality. We are creatures forever caught between security and adventure, tradition and innovation, certainty and mystery. His genius lies in reframing this tension not as pathology but as the arena of meaning-making.

The stories that endure across cultures—heroes descending into darkness (Chaos) to retrieve wisdom (New Order)—are not mere myths. They are roadmaps for existence. Peterson’s clinical work with trauma survivors reveals this pattern empirically: those who “voluntarily confront the dragon” of their suffering emerge not unscathed but enlarged.

In a fragmented world seduced by simplistic ideologies, Peterson’s call for balanced responsibility remains bracingly countercultural. His legacy, still unfolding, may ultimately reside in restoring psychology’s original mandate: not just alleviating suffering, but guiding souls in the eternal dance between darkness and light—where meaning is forged in the crucible of courageous existence. As he concludes in Maps of Meaning:

“The most profound truths are written in the oldest stories. Our task isn’t to escape them, but to decipher their code and live them anew“.

On August 20, 2018, a slight 15-year-old girl sat alone on the cobblestones outside Sweden’s parliament building. Her hand-painted sign read “Skolstrejk för Klimatet” (School Strike for Climate). Then Greta Thunberg solitary vigil began. After Sweden’s hottest summer in 262 years—a season of heatwaves and wildfires that screamed climate emergency. Here “I want to feel safe,” she had written months earlier in a winning essay for Svenska Dagbladet. And “How can I feel safe when I know we are in the greatest crisis in human history?”

Within weeks, her whisper ignited a global roar. By September 2018, what started as a one-girl protest exploded into the #FridaysForFuture movement—millions of young people abandoning classrooms to demand planetary salvation. Completely, this is the story of how an “ordinary” teenager diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome weaponised her difference. Turned family trauma into global action. And forced world leaders to confront an inconvenient avalanche.

For the first time, Greta encountered climate change at age eight. While her classmates absorbed fairy tales, she consumed graphs of carbon emissions and species extinction rates. Then dissonance haunted her: “If the oceans die, we die. Why was no one acting like this was an emergency?”. By 11, the weight of impending collapse triggered severe depression. So she stopped speaking, eating, and attending school. Her opera singer mother, Malena Ernman, recalled: She cried on her way to school. But slowly disappearing into darkness .

Here diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, OCD, and selective mutism, Greta found her voice through crisis. That’s why she called her neurodivergence a “superpower”: “If I would’ve been like everyone else, I wouldn’t have started this school strike”. Best of all, laser focus on climate science became her lifeline. And she weaponised it at home first. For two years, she bombarded her parents with data. Then demanding that they become vegan, upcycle, and abandon air travel. Her ultimatum cut deep: “You are stealing my future” .

Armed with leaflets citing 30 scientific sources, 15-year-old Greta launched her strike despite parental resistance. Here Svante Thunberg confessed: “We said, ‘If you do this, you’re alone.’ So we thought social media would destroy her” . On Day 1, journalists ignored her. On Day 3, a stranger gave her vegan pad thai—a moment her father calls mystical: “She changed. In her life, she could do things she’d never done before” .

Then, a viral Instagram post. Then hundreds. Then thousands. By election day, she wasn’t alone. Then #FridaysForFuture hashtag was born. And students from Brussels to Sydney joined the sit-ins. Reaction of Greta’s ?. When one person joined me on Day 2, I knew, I could make a difference .

| Date | Event | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| August 20, 2018 | Solo strike outside Swedish Parliament | 1 protester |

| September 2018 | First global climate strike | 100+ cities |

| March 2019 | Coordinated multi-city marches | 1.5 million+ protesters |

| September 2019 | Global Climate Strike | 4 million+ across 163 countries |

Here oratory of Greta’s fused scientific precision with raw moral fury. At Davos 2019, she discarded hope for panic: “I want you to act as if your house was on fire. Because it is”. In the EU Parliament, she branded climate inaction “the greatest failure of human history”. Her style was deliberate: monotone delivery, facts over flair. So that eyes locking onto leaders like scalpels.

In the month of August, 2019, Greta sailed emissions-free across the Atlantic (a 15-day voyage) to confront world leaders at the UN Climate Action Summit. So her 4-minute speech detonated like a moral grenade :

“You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words… We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!”

Here philosopher Peter Singer called it “the most powerful four-minute speech I’ve ever heard.” Sarcastically Donald Trump tweeted: “She seems like a very happy young girl”. Prompting Greta to update her Twitter bio: “A very happy young girl looking forward to a bright and wonderful future”. Then the phrase “How dare you” became an anthem, remixed into death metal songs and DJ Fatboy Slim tracks .

| Element | Content | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Opening Hook | “This is all wrong. I shouldn’t be here” | Framed as a stolen childhood |

| Moral Charge | “You have stolen my dreams” | Personalized intergenerational injustice |

| Scientific Proof | “420 gigatons of CO2 budget left (2018)” | Undercut political vagueness with data |

| Call to Arms | “We will never forgive you” | Mobilized youth solidarity |

Across 7500 cities by 2023, Fridays for Future had mobilized over 13 million strikers. So compassionately, the “Greta effect” measurable:

Yeah own way, Greta’s rise magnetised vitriol:

Through it all, her compass held true. Then arrested for blocking oil facilities. But she declared, “We are the necessary troublemakers.”

Behind that Greta’s steeliness lies a family transformed. Her father, Svante, joined her sail to New York “not to save the climate—to save my daughter”. Her mother abandoned international opera tours, adopting near-veganism. Yet Greta refused guilt: “It was their choice. I just gave them information”.

In 2023 majorly, graduating high school didn’t slow her. Instead, Greta evolved:

Here one of the most, she redefined power. As well as most cases, no office, no fortune, no weapons—just a girl who refused to beg. Her only way of genius lay in inverting the narrative: children became the adults in the room.

When critics sneered at her “anger”. Then she retorted, “What is anger but care in overdrive?”. When they dismissed her as a puppet. Her TEDx talk clarified, “I don’t want your hope. So I want you to panic and act”.

Today, as wildfires rage and glaciers weep. Her warning echoes: “The world is waking up. Change is coming—whether you like it or not”. In that civilisation hypnotised by growth, Greta is the alarm clock we cannot snooze. Her greatest lesson?

“No one is too small to make a difference.”

— Those words that launched a million strikes, and maybe, a future.

On January 3, 2023, Greta turned 21. No fanfare, no retreat. Still striking, still speaking truth to trembling power. To her parents, she’s finally “an ordinary child”—dancing, laughing, healing . To Earth’s children, she’s the extraordinary voice that taught them: In a world on fire, “different” is the superpower that lights the way.