Latest News

My latest ramblings.

Enjoy! I definitely got important things to say

My latest ramblings.

Enjoy! I definitely got important things to say

Avicenna: Philosopher & Physician – The Polymath Who Healed Knowledge and Bodies

But what makes Avicenna trending today? In an age debating artificial intelligence, medical ethics, and the unity of science and spirituality, Avicenna’s integrative thinking provides a roadmap: science without philosophy is blind, philosophy without science is empty, and medicine without ethics is incomplete.

This blog takes you through Avicenna’s life, philosophy, medicine, and legacy, weaving in historical anecdotes and modern reflections, to show why his thought still matters—and why his name keeps resurfacing in global conversations.

Avicenna was born near Bukhara (modern Uzbekistan) in 980 CE. His father, a tax official, ensured his son had access to education. By age 10, the young boy had memorized the Qur’an and mastered classical Arabic—a feat that would foreshadow his lifelong devotion to learning.

As a teenager, he studied logic, geometry, astronomy, and metaphysics under local scholars, quickly surpassing them. By 16, Avicenna claimed to have fully grasped medicine, calling it “not difficult compared to mathematics and metaphysics.” Soon after, he began practicing as a physician—gaining fame not only for his skill in diagnosis but also for his gentle approach with patients.

At just 17 years old, Avicenna successfully treated the Samanid ruler Nuh ibn Mansur, earning access to the royal library in Bukhara. This was transformative: inside lay rare Greek, Indian, and Persian manuscripts, which Avicenna devoured. From this treasure trove, he forged the foundations of his encyclopedic knowledge.

Avicenna believed philosophy was not merely an abstract pursuit—it was a medicine for the soul. His works sought to unify Aristotle’s rationalism, Neoplatonism’s spirituality, and Islamic theology into a coherent system.

Despite its title, this was not a medical text. The Book of Healing (Kitāb al-Shifāʾ) was a sprawling encyclopedia covering logic, natural sciences, mathematics, psychology, and metaphysics. It aimed to “heal” ignorance by providing intellectual clarity.

Within it, Avicenna explored:

Avicenna’s most famous philosophical idea is the Flying Man thought experiment. He asked us to imagine a man created fully formed, floating in mid-air, blindfolded, with no sensory contact. Would he be aware of his own existence? Avicenna argued yes—the man would have an innate awareness of his soul, independent of the body.

This experiment anticipated later debates on consciousness, influencing both Islamic philosophers and European thinkers like Descartes. Today, neuroscientists and AI ethicists revisit the Flying Man as an early probe into the mystery of self-awareness.

Unlike some rationalists, Avicenna did not reject religion. He saw philosophy and faith as complementary: reason clarified divine truths, while revelation grounded human understanding in morality. His synthesis influenced Islamic theology, Christian Scholasticism, and even Jewish philosophy through figures like Maimonides.

If Avicenna’s philosophy healed the soul, his medicine healed the body. His most enduring legacy in this realm is The Canon of Medicine (al-Qānūn fī al-ṭibb), completed around 1025.

This five-volume masterpiece systematized centuries of medical knowledge—from Hippocrates and Galen to Indian and Persian traditions. But Avicenna didn’t just compile; he critiqued, reorganized, and added original insights.

Key contributions include:

The Canon became the standard medical text in Europe for over 600 years, studied in universities like Montpellier and Padua until the 17th century.

Avicenna viewed health as a balance of body and soul. He described cases of melancholia (depression), recognizing psychological factors in illness. One famous anecdote tells of a prince suffering from lovesickness; Avicenna diagnosed the cause by observing changes in the young man’s pulse as different names were mentioned, eventually curing him through counseling.

In this way, Avicenna foreshadowed psychosomatic medicine and even modern psychiatry.

Though limited by the religious restrictions of his time, Avicenna’s anatomical descriptions were remarkably precise. He distinguished nerves from tendons, emphasized the importance of the spinal cord, and proposed surgical methods like nerve repair—ideas centuries ahead of his era.

Avicenna was fascinated by the cosmos. He theorized about the nature of stars, the Milky Way, and planetary motion. Some historians believe he may have observed the supernova of 1006, the brightest stellar event in recorded history.

In physics, he challenged Aristotelian mechanics, developing ideas resembling the modern concept of inertia. His notion that an object in motion remains in motion unless acted upon prefigured Newton’s first law.

Avicenna experimented with distillation, creating methods to extract essential oils from flowers. This not only influenced perfumery but also laid groundwork for chemistry and pharmacology.

Avicenna became a central figure in Islamic philosophy (falsafa). Schools of thought debated his ideas for centuries. Theologians like al-Ghazālī criticized him, while philosophers like Suhrawardī and Mullā Ṣadrā extended his insights.

Through Latin translations, Avicenna shaped European thought. His Canon of Medicine was a staple in medical schools, while his metaphysics influenced Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Magnus, and the entire Scholastic tradition.

– UNESCO’s Avicenna Prize for Ethics in Science (est. 2003) honors scientists advancing ethical reflection.

– A crater on the Moon and an asteroid bear his name.

– His works continue to be studied in philosophy, history of science, and medical ethics programs worldwide.

Why revisit Avicenna now? Because his life embodies principles we urgently need:

Avicenna’s genius was not just in mastering diverse fields, but in unifying them. For him, healing meant more than curing a fever or setting a bone—it meant restoring harmony between body, mind, and soul.

In a world fractured between science and spirituality, ethics and technology, East and West, Avicenna’s vision offers a powerful reminder: wisdom is not the possession of one culture but the shared inheritance of humanity.

The fact that his name trends over a thousand years after his death is not nostalgia—it’s relevance. Avicenna speaks to our time because he understood what makes us whole.

Few poets in world history have captured the imagination of humanity across cultures, faiths, and centuries as profoundly as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī (1207–1273). Known to the Persianate world as Mawlānā (“Our Master”) and to the West simply as Rumi, he was not only a poet but also a jurist, theologian, Sufi mystic, and spiritual teacher whose words continue to echo in mosques, monasteries, libraries, and living rooms worldwide. His writings, composed in Persian with inflections of Arabic, Turkish, and Greek, comprise some of the most celebrated works of Islamic mysticism: the Masnavi-ye Ma‘navi (Spiritual Couplets), often described as a “Persian Qur’an,” and the Divan-e Shams-e Tabrīzī, a vast compendium of ecstatic lyric poetry inspired by his beloved friend and guide, Shams.

To understand Rumi, however, one must situate him in his tumultuous historical moment — an era marked by Mongol invasions, shifting empires, and spiritual crosscurrents. His life was a journey from Balkh to Konya, from jurist to mystic, from scholar to poet of the heart. At its center stands the transformative force of divine love — a love that dissolved boundaries between faiths, cultures, and languages.

This biography presents a detailed exploration of Rumi’s life and legacy, moving through his upbringing, education, pivotal encounters, literary production, teachings, and enduring influence.

Rumi was born on 30 September 1207 in the city of Balkh, a major center of learning and culture in the Persianate world (present-day Afghanistan). His full name was Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn Ḥusayn al-Balkhī. The epithet Rumi (“from Rum”) was attached later, referencing Anatolia — called “Rum” by Muslims because it had been part of the Byzantine (Roman) Empire.

Rumi’s father, Bahāʾ al-Dīn Valad, was a renowned preacher, jurist, and mystic in Balkh, nicknamed Sultan al-ʿUlamāʾ (“Sultan of the Scholars”). His teachings blended Islamic jurisprudence with mystical reflection, laying a foundation for the young Jalāl al-Dīn’s dual identity as both scholar and seeker. His mother, believed to be of noble Khwarezmian descent, nurtured the household with refinement and devotion.

In Rumi’s youth, Central Asia was a cauldron of instability. The Mongol armies under Genghis Khan were sweeping westward, devastating cities such as Samarkand and Bukhara. Sensing the impending danger, Bahāʾ al-Dīn led his family on a long migration westward. They traveled through Nishapur — where the young Rumi is said to have met the poet ʿAttār — then Baghdad, Damascus, and Mecca on pilgrimage, before finally settling around 1228 in Konya, capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. It was here that Rumi would spend most of his life.

Rumi’s early education followed the classical curriculum of Islamic scholarship: Qur’anic studies, Hadith, Arabic grammar, Islamic jurisprudence, and theology. His father served as his first teacher. When Bahāʾ al-Dīn died in 1231, his followers and patrons looked to Jalāl al-Dīn to inherit his mantle. Though still young, Rumi assumed leadership and became the head of a madrasah in Konya, teaching law, issuing legal opinions, and delivering sermons.

Rumi was not only a jurist but also a theologian well-versed in the intellectual currents of his time. He pursued further training in Aleppo and Damascus, two centers of advanced Islamic learning. In Damascus, he encountered leading scholars and Sufi teachers, refining his mastery of both exoteric knowledge and esoteric wisdom. By the 1240s, Rumi was widely respected in Konya as a sober and learned scholar. Yet beneath this respectable exterior stirred a yearning for a deeper, more direct experience of divine reality — a yearning that would find its answer in the figure of Shams al-Dīn of Tabriz.

The pivotal moment in Rumi’s life occurred in November 1244, when he met Shams al-Dīn Tabrīzī, a wandering dervish of fiery temperament and uncompromising spirituality. Shams was eccentric, unconventional, and utterly devoted to the quest for God. The two men formed an intense spiritual companionship. Rumi abandoned much of his teaching and juristic duties, spending long hours in secluded dialogue with Shams. He described Shams not merely as a friend but as a mirror of the Divine Beloved. Their conversations sparked in Rumi a torrent of mystical experience, which poured forth in ecstatic verse.

This radical shift alarmed many of Rumi’s students and family, who resented Shams’ influence. After only a year, Shams disappeared — possibly fleeing hostility, possibly murdered by jealous disciples in 1247 or 1248. His disappearance devastated Rumi. Yet from that grief emerged one of the most extraordinary literary transformations in history: Rumi turned his longing for Shams into poetry that voiced the soul’s longing for God.

In memory of Shams, Rumi composed a vast collection of lyric poetry — ghazals, qasidas, and quatrains totaling more than 40,000 lines. Known as the Divan-e Shams-e Tabrīzī, the work is not merely a personal elegy but a monumental celebration of mystical love. In these poems, Shams is both the human friend and the symbol of the Divine. The imagery is ecstatic — wine, music, dance, fire, and union all serve as metaphors for the annihilation of the self in God.

Between 1260 and 1273, Rumi dictated his magnum opus, the Masnavi, to his disciple Husam al-Din Chelebi. Comprising six books and about 25,000 couplets, the Masnavi blends parables, anecdotes, Qur’anic exegesis, and mystical allegories. It is at once a spiritual commentary on the Qur’an and a practical manual for seekers on the Sufi path. The text covers themes of divine love, self-purification, humility, and union with the Beloved, and for centuries has been studied as “the Persian Qur’an.”

This prose work compiles Rumi’s discourses given to his disciples. Less ornamented than the poetry, Fihi Ma Fihi provides direct insight into his thought: reflections on metaphysics, the role of the spiritual master, the nature of the soul, and the ultimate reality of God.

Rumi also left behind letters to nobles, disciples, and family members. These reveal his role as a community leader, mediator, and spiritual guide. They show that while his poetry soared to mystical heights, he remained engaged in the practical affairs of Konya.

At the heart of Rumi’s thought is love (ʿishq). Love is the force that moves the universe, the bridge between human and divine, the energy that transforms pain into beauty. For Rumi, every form of love — for a teacher, a friend, or humanity — is a reflection of the Divine Love that sustains existence.

Rumi’s poetry constantly circles around the paradox of separation and union. The soul, exiled from its source, longs for reunion with God, like the reed flute that laments its separation from the reed bed. This longing, while painful, is also the engine of spiritual growth.

Wine, taverns, music, dance, and intoxication serve as metaphors for spiritual ecstasy. Fire represents both destruction of the ego and illumination of the soul. The lover–beloved imagery expresses the relationship between human and Divine. These symbols allow Rumi to communicate experiences beyond the reach of discursive theology.

While often celebrated today as a universal mystic, Rumi was deeply rooted in Islam. The Qur’an and Hadith permeate his works, and he consistently framed his mystical vision within Islamic concepts of tawḥīd (Divine unity), prophecy, and ethical living. The Masnavi was considered by his contemporaries a continuation of Islamic spiritual commentary.

After Shams’ disappearance, Rumi deepened his role as a teacher and spiritual guide. With Husam al-Din Chelebi and later his son Sultan Walad, he gathered a community of disciples that would crystallize into the Mevlevi Order, known for its whirling dance (sema) symbolizing the soul’s ascent toward God.

Rumi’s gatherings in Konya were remarkable for their inclusivity. Muslims, Christians, and Jews attended his sermons, drawn by his universal language of love. His school combined scholarship with spiritual practice, making Konya a beacon of learning and devotion.

Rumi passed away on 17 December 1273 in Konya. His funeral drew a vast crowd of Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others, each group claiming him as their own. His mausoleum, the Green Dome (Kubbe-i Hadra), remains a major pilgrimage site in Konya, now part of the Mevlana Museum.

After his death, his followers formalized his teachings into the Mevlevi Sufi order. The “whirling dervishes” became a distinctive expression of his mystical heritage, combining poetry, music, and dance as spiritual practice. His son, Sultan Walad, composed works preserving his father’s legacy and institutionalizing the order.

Over the centuries, Rumi’s influence has only grown. In the Persianate world, he shaped the mystical literature of Iran, Turkey, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. Figures like Hafez, Jami, and Iqbal drew inspiration from him. In Ottoman Turkey, the Mevlevis became patrons of art, music, and literature.

In the modern West, translations — especially those by Coleman Barks — have popularized Rumi as a best‑selling poet, though often stripped of explicit Islamic context. This has sparked debate: some celebrate his universal accessibility, while others stress the importance of recognizing his Islamic and Sufi roots. Nevertheless, Rumi speaks across divides. His words on love, longing, humility, and unity resonate with secular seekers and religious devotees alike. He stands as a bridge between East and West, faith and reason, mysticism and poetry.

Rumi’s life was a journey of transformation: from jurist to mystic, from scholar to poet, from Balkh to Konya, from the grief of loss to the ecstasy of divine love. His writings remain among the most profound expressions of the human soul’s search for God. At the core of his message is a simple yet inexhaustible truth: Love is the essence of all existence. Today, more than 800 years after his death, Rumi continues to invite us to enter the circle of love, to whirl with the dervishes, to listen to the flute’s lament, and to remember the Beloved.

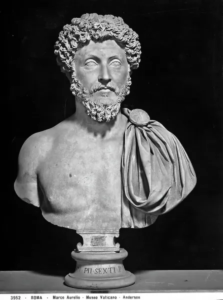

The Roman Empire had many leaders, but Marcus Aurelius stands out. He was a philosopher-king who lived by Stoic principles.

Marcus Aurelius, a Stoic Emperor, ruled the Roman Empire with wisdom. He left behind a wealth of philosophical thoughts in his writings.

His time in power is a great lesson in leadership and philosophy. It shows us how to face life’s challenges.

Marcus Aurelius was born on April 26, 121 AD. He came from a noble Roman family. His upbringing was a mix of luxury and hard study, common for the aristocracy.

His father, Marcus Annius Verus, was rich and influential. His mother’s family, the Calvisii, was also well-respected. This made Marcus‘s start in life very promising.

Marcus grew up with the power and duties of nobility around him. He was taught both books and fighting, preparing him for leadership.

His childhood taught him about duty, honor, and learning. These lessons shaped his later love for Stoicism.

Marcus Aurelius‘s education was key in shaping his thoughts and leadership. He learned from many tutors, each influencing his views and actions.

Marcus Aurelius had several important tutors. Marcus Cornelius Fronto, a famous orator and lawyer, taught him about rhetoric and hard work. Fronto’s lessons on diligence and integrity deeply affected Marcus Aurelius.

Junius Rusticus introduced Marcus Aurelius to Stoicism through Epictetus’s works. This exposure deeply influenced Marcus Aurelius, shaping his Stoic beliefs and leadership approach.

Marcus Aurelius was also exposed to other philosophies. His education was diverse, covering many perspectives. This broadened his understanding of the world.

Marcus Aurelius‘s adoption by Antoninus Pius in 138 AD was a key moment. It started his journey to become emperor.

Antoninus Pius, chosen by Emperor Hadrian, adopted Marcus Aurelius and his brother Lucius Verus. This move was strategic. It ensured Marcus Aurelius‘s future role.

Under Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius learned politics, philosophy, and military affairs. He was prepared for leadership, taking on roles in the Roman administration.

Marcus Aurelius‘s time under Antoninus Pius was very valuable. He learned by attending senate meetings and making important decisions. This training helped him face the challenges of being emperor.

The year 161 AD was a turning point for Marcus Aurelius as he took the throne with Lucius Verus. This started a new chapter for the Roman Empire, with Marcus Aurelius leading the way.

Marcus Aurelius became emperor after Antoninus Pius adopted him. This was a common practice in Rome to ensure a smooth transition. It showed the empire’s commitment to stability and continuity.

Marcus Aurelius chose to rule alongside Lucius Verus, whom he also adopted. This was a bold move, aiming to strengthen the empire’s leadership. Yet, it brought its own set of challenges due to their different personalities and governance styles.

Marcus Aurelius faced many challenges early in his reign. The empire was threatened by neighboring tribes and needed to stay prosperous and stable internally.

| Challenge | Description | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| External Pressures | Threats from neighboring tribes | Successful defense and strategic alliances |

| Internal Issues | Administrative and economic challenges | Reforms and adjustments to governance |

Marcus Aurelius tackled these challenges with his usual stoic strength. His early years as emperor showed his ability to balance leadership with his deep commitment to Stoic philosophy.

Marcus Aurelius brought many reforms to his rule, showing his Stoic values. He aimed for justice, fairness, and the happiness of his people.

He made laws simpler and fair for everyone. He also helped the poor and supported education.

He worked hard to keep the economy stable. He invested in projects to grow the economy.

His Stoic beliefs shaped how he ruled. He sought to be just and wise in his decisions.

| Reform Area | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Reforms | Simplified legal procedures, equal application of law | Improved justice system |

| Social Policies | Aid to the poor, promotion of education | Enhanced social welfare |

| Economic Management | Currency stabilization, infrastructure investment | Economic growth and stability |

Marcus, a Stoic emperor, faced many challenges during his reign. He dealt with wars and plagues that hit the Roman Empire hard. His leadership and beliefs were tested by these significant military battles.

The Parthian War started in 161 AD. It was sparked by a Parthian invasion of Armenia, a Roman ally. Marcus Aurelius sent troops, led by co-emperor Lucius Verus, to the area.

The Marcomannic Wars lasted from 166 to 180 AD. Germanic tribes, like the Marcomanni and Quadi, threatened the empire’s safety. Marcus Aurelius led the Roman forces, using his Stoic beliefs to cope with war’s hardships.

The Antonine Plague hit during Marcus Aurelius‘s rule. It greatly reduced the Roman population, affecting the military and economy.

The wars and plague weakened the Roman Empire. The loss of people and economic troubles had lasting effects on the empire’s stability.

Marcus Aurelius‘s response to these crises is seen in his Meditations. He emphasized the need for resilience and inner strength. His Stoic philosophy guided him as a leader.

| Crisis | Impact | Marcus Aurelius’s Response |

|---|---|---|

| Parthian War | Strained military resources | Led by example, supported Lucius Verus |

| Marcomannic Wars | Threatened Danube frontier | Personally led campaigns, applied Stoic resilience |

| Antonine Plague | Significant population loss, economic disruption | Reflected on impermanence of life in Meditations |

Marcus Aurelius‘s life was a mix of duty, family, and deep thinking. As a Stoic Emperor, he ruled the Roman Empire while staying true to his beliefs.

Marcus Aurelius married Annia Galeria Faustina, known as Faustina the Younger. Their marriage was arranged, common among the Roman elite. Yet, they had a lasting bond until Faustina’s passing. Faustina was admired for her beauty and strength, and they had many children together.

They had at least 13 kids, but only a few grew up. Their children included Commodus, who became emperor after Marcus Aurelius. Family was key to Marcus Aurelius‘s life, balancing family with his duties was tough.

He followed Stoic philosophy in all he did, as a ruler and family man.

Some of his habits were:

These habits showed his strong character and values.

Marcus Aurelius‘s “Meditations” is a key part of Stoic philosophy. It gives us a look into the mind of a Roman emperor. This collection of personal thoughts and prayers shows how Stoic ideas can guide leadership and everyday life.

“Meditations” was written by Marcus during his military campaigns, from 170-180 AD. It was meant for his own guidance, not for the public. It shows the emperor’s dedication to Stoicism and his efforts to live by its principles.

The “Meditations” is divided into 12 books, each covering different Stoic topics. The entries are short and to the point, focusing on virtue, morality, and the universe. It’s a deeply personal work, showing the emperor’s inner struggles and his search for wisdom.

The “Meditations” explores important Stoic ideas like virtue, morality, nature, and cosmic order. These themes are woven throughout, giving a full picture of Stoic thought.

| Concept | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Virtue | Living in accordance with reason and nature | Guides moral character and actions |

| Morality | Principles guiding human behavior | Essential for personal and societal harmony |

| Nature | The natural world and its order | Provides a framework for understanding the universe |

| Cosmic Order | The rational structure of the universe | Underlies the Stoic view of reality |

In conclusion, “Meditations” by Aurelius is a treasure trove of Stoic philosophy. It offers insights into a leader who tried to live by Stoic principles. Through its exploration of virtue, morality, nature, and cosmic order, it continues to inspire and guide those seeking wisdom and a deeper understanding of life.

Marcus was a philosopher-emperor who lived by Stoicism. He used its teachings to lead his empire. His life shows how valuable Stoic philosophy is for leaders and individuals.

Stoicism believes in reason, self-control, and not caring about things outside of our control. Marcus followed these ideas. He focused on what he could control, like his reactions, not external events.

The philosophy also teaches living in harmony with nature and accepting things we can’t change. This helped Marcus stay calm during tough times, like wars and plagues.

Marcus was a just

Every year, as the monsoon clouds begin to part over India, streets and homes burst into color, chants of Ganapati Bappa Morya echo through neighborhoods, and the scent of incense mingles with fresh modaks. This is the season of Ganesh Utsav, a celebration of Lord Ganesha, the elephant-headed deity revered as the remover of obstacles, the harbinger of wisdom, and the patron of arts and sciences.

But Ganesh Utsav is not merely a festival. It is a multi-layered cultural phenomenon—a blend of myth, devotion, politics, community, art, and even environmental consciousness. From its ancient Vedic roots to its reinvention during India’s freedom struggle, and from intimate household rituals to massive global processions, the festival reveals how faith and tradition continuously adapt to changing times.

This blog dives deep into the history, symbolism, rituals, controversies, and modern transformations of Ganesh Utsav, while also reflecting on its timeless relevance in a fast-paced globalized world.

The story of Ganesha’s creation is as fascinating as his form. According to the Shiva Purana, Goddess Parvati fashioned him from turmeric paste as a guardian for her chambers. When Lord Shiva returned and found the boy blocking his entry, a furious battle ensued, ending with Shiva severing Ganesha’s head. To console Parvati’s grief, Shiva replaced it with an elephant’s head, granting the boy immortality as the foremost deity of worship.

This myth is layered with symbolism—Ganesha’s head signifies wisdom, his large ears receptivity, his broken tusk sacrifice, and his potbelly the universe itself. Unlike many deities, Ganesha transcends sectarian boundaries and is worshiped across Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Shaktism, Jainism, and even Buddhism.

The earliest known references to Ganesha date back to the Gupta period (4th–6th century CE), when he emerged as a distinct deity. Archeological evidence of Ganesha idols has been found across India, Nepal, Cambodia, and Indonesia, revealing how Indian culture spread through trade and pilgrimage.

By the medieval period, Ganesha became the “Vighnaharta” (remover of obstacles), invoked at the beginning of rituals, journeys, and new ventures—an enduring practice that survives in homes and businesses today.

Ganesh Chaturthi, marking Ganesha’s birthday, was historically celebrated in private households. Families would craft clay idols, perform puja, and immerse the deity in water after the rituals.

The festival underwent a radical transformation in 1893, when freedom fighter Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak turned Ganesh Utsav into a public celebration. At a time when the British banned political gatherings, Tilak cleverly used the religious festival as a platform to foster unity, nationalism, and social reform.

Large pandals (temporary shrines) sprang up across Maharashtra, where people gathered for prayers, debates, plays, and patriotic songs. What began as devotion became a tool of resistance and empowerment—a reminder that festivals are not just rituals, but catalysts of social change.

The festival begins with the installation of clay idols of Ganesha in homes and pandals. The ritual of pranapratishtha—infusing divine life into the idol—is performed by priests chanting Vedic mantras.

The deity is offered 21 durva grass blades, 21 modaks, red hibiscus flowers, coconut, and jaggery. Each offering carries symbolic meaning—modaks as rewards of wisdom, grass as humility, and hibiscus as energy.

Morning and evening aartis (devotional songs) are performed with drums, bells, and chants. In public pandals, cultural programs, bhajan sessions, yoga camps, and even blood donation drives take place—blending spirituality with social service.

The final day, Anant Chaturdashi, witnesses massive processions carrying the idol for immersion (visarjan) in rivers, lakes, or seas. The immersion symbolizes the cycle of creation and dissolution, teaching detachment and renewal.

Ganesh Utsav fuels artistic creativity—giant pandals with elaborate themes, from mythology to modern issues like climate change. Traditional instruments like dhol-tasha electrify processions, while devotional songs like Sukhkarta Dukhaharta echo across gatherings.

The festival is incomplete without modaks, considered Ganesha’s favorite sweet. Each region adds its twist—fried modaks in Maharashtra, steamed kozhukattai in Tamil Nadu, or coconut-stuffed ukadiche modak. The food signifies gratitude and community sharing.

Every part of Ganesha’s form teaches a lesson:

The idol itself is a philosophical text in form—a reminder that spirituality is embedded in everyday life.

The grandeur of Ganesh Utsav has raised serious environmental issues: plaster of Paris idols, chemical paints, and plastic decorations pollute rivers and harm marine life.

In response, many communities are embracing:

This shift reflects how festivals evolve with contemporary concerns, proving spirituality and ecology can go hand in hand.

Despite its popularity, Ganesh Utsav is not without debates:

These debates highlight the tension between tradition and modernity, faith and commercialization.

Today, Ganesh Utsav has transcended borders. In places like London, Toronto, and Sydney, immigrant communities recreate the festival, inviting locals to join in. The deity of beginnings has become an ambassador of Indian soft power, spreading cultural diplomacy across continents.

Interestingly, Ganesha has also entered pop culture—appearing in yoga studios, tattoos, contemporary art, and even business boardrooms as a symbol of prosperity and success.

Psychologists note that festivals like Ganesh Utsav fulfill deep human needs for community, identity, and renewal. The rituals provide structure, the chants create collective energy, and the immersion ritual teaches detachment.

Sociologically, Ganesh Utsav acts as a social glue—cutting across caste, class, and even religious boundaries in many places. It exemplifies how shared traditions strengthen social cohesion in times of rapid change.

Ganesh Utsav is not just about tradition but about timeless lessons for modern life:

From a household ritual in ancient India to a nationalist movement under Tilak, and from community pandals in Mumbai to eco-conscious celebrations worldwide, Ganesh Utsav has continually reinvented itself while retaining its spiritual essence.

At its heart, the festival celebrates not only the deity but also the human capacity to unite, create, and transform. It is a reminder that true devotion lies not just in rituals but in embodying Ganesha’s qualities—wisdom, humility, adaptability, and compassion.

As the chants fade and the idols dissolve into rivers, what remains is the festival’s deeper message: every ending is a new beginning. In a world of constant uncertainty, Ganesh Utsav continues to teach us resilience, renewal, and the power of collective spirit.

Ganapati Bappa Morya!

In the annals of human history, few figures have wielded intellectual influence as enduring as Chanakya (c. 370-273 BCE), the ancient Indian philosopher, strategist, and kingmaker. Known also as Kautilya and Vishnugupta, this visionary thinker crafted political frameworks that would establish one of history’s most formidable empires—the Mauryan Empire—while producing timeless works on statecraft, economics, and human behavior that remain startlingly relevant more than two millennia later. Yet, for all his celebrated contributions, Chanakya remains an enigmatic figure, shrouded in mystery and contradiction. This comprehensive exploration delves beyond popular knowledge to reveal the lesser-known facts, controversies, and enduring legacy of a man whose strategic genius continues to influence fields from political theory to modern business management.

Surprisingly, the historical existence of Chanakya remains a subject of scholarly debate. Contemporary Greek records, including Megasthenes’ Indica (written during his decade-long stay in Chandragupta Maurya’s court), make no mention of Chanakya whatsoever . This absence has led some historians to question whether Chanakya was indeed a historical figure or rather a composite literary character representing political wisdom. The earliest written records of Chanakya appear in the 8th-century Prakrit drama Mudra Rakshasa by Vishakhadatta, written approximately 1,200 years after Chandragupta’s reign . This temporal gap has fueled ongoing historical controversies about the accurate timeline of events and figures during this period.

The historical documentation presents contrasting perspectives on Chanakya’s life and influence:

Table: Historical Accounts of Chanakya

| Source | Period | Details Provided | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greek Records (Megasthenes) | 4th century BCE | Detailed account of Mauryan court but no mention of Chanakya | Focused on contemporary events rather than advisors |

| Jain Texts | 4th-5th century CE | Personal life details and Jain affiliation | Written centuries after Chanakya’s death |

| Buddhist Texts | 5th-6th century CE | Taxila education and role in establishing Mauryan rule | Regional biases and mythological elements |

| Mudra Rakshasa | 8th century CE | Political activities during Mauryan establishment | No personal life details; primarily dramatic narrative |

According to Jain texts, Chanakya was born to Chanak, a devout Jain, and entered the world with a full set of teeth—a sign believed to predict kingship . Since this was considered inappropriate for a Brahmin family, his father broke the teeth, with a Jain monk predicting that the child would instead become a kingmaker . As a child, he demonstrated extraordinary academic capabilities and stubborn determination, though he was not considered good-looking, which made finding a bride difficult . He eventually married a poor girl named Yashomati .

Chanakya studied at Taxila University, one of the ancient world’s premier educational institutions, where he mastered diverse subjects including Vedas, politics, economics, military strategy, and astronomy . The university accommodated over 10,000 students and offered courses spanning more than eight years, with specialized studies in science, philosophy, Ayurveda, grammar, mathematics, economics, astrology, geography, astronomy, surgical science, agricultural sciences, archery, and ancient and modern sciences . It was here that Chanakya began developing his revolutionary ideas about statecraft and administration.

In a remarkable parallel to his protégé Chandragupta Maurya, Chanakya allegedly embraced Jainism in his later years . According to Jain accounts, he retired from ministership to become a Jain monk and met his end through a tragic fire in the jungle where he was meditating—set ablaze by a minister of Bindusara (Chandragupta’s son) who held grudges against him . This little-known account contradicts popular perceptions of Chanakya as a purely political animal without spiritual dimension.

The meeting between Chanakya and Chandragupta Maurya represents one of history’s most consequential mentor-protégé partnerships. Multiple accounts suggest Chandragupta came from extremely humble origins—possibly even being sold into slavery as a child . Chanakya reportedly encountered the young Chandragupta demonstrating natural leadership qualities among his fellow slaves and recognized his potential . In a decisive moment, the philosopher purchased the slave boy from his owner (a hunter) and took him to Taxila to be educated in the arts of governance and warfare .

The popular narrative of Chanakya’s oath against the Nanda dynasty finds support in multiple historical traditions. After being publicly insulted by Dhana Nanda, the ruler of Magadha, Chanakya reportedly untied his shikha (sacred hair tuft), vowing not to retie it until he had uprooted the Nanda king and established a united and fortified India . This powerful symbolic gesture demonstrated his extraordinary determination and became the driving force behind his political machinations.

Chanakya’s Niti Shastra contains fascinating insights into his strategic philosophy, particularly his advice on learning from animal behavior . In Chapter 6, he articulates specific qualities to emulate from various creatures:

Table: Chanakya’s Animal-Inspired Strategic Principles

| Animal | Number of Qualities | Qualities to Emulate |

|---|---|---|

| Lion | 1 | Whatever one intends to do should be done with whole-hearted and strenuous effort |

| Crane | 1 | Restrain senses and accomplish purposes with knowledge of place, time, and ability |

| Cock | 4 | Wake at proper time; take bold stand and fight; make fair division among relations; earn bread by personal exertion |

| Crow | 5 | Union in privacy; boldness; storing useful items; watchfulness; not easily trusting others |

| Dog | 6 | Contentment with little eating; instant awakening; unflinching devotion to master; bravery |

| Ass | 3 | Continue carrying burden despite fatigue; unmindful of cold and heat; always contented |

Chanakya claimed that practicing these twenty virtues would make a person invincible in all undertakings .

Chanakya’s political philosophy found practical expression in the Mauryan Empire’s administrative structure, which featured remarkable innovations:

The Greek diplomat Megasthenes, who spent four years at Pataliputra, documented an empire far more orderly and well-run than any contemporary Greek state, effectively corroborating the policies articulated in Chanakya’s Arthashastra .

Often called the “Indian Machiavelli” though predating the Italian philosopher by approximately 1,800 years, Chanakya actually presented a much more comprehensive vision of governance . His Arthashastra covers:

The text was lost near the end of the Gupta dynasty and only rediscovered in 1915, dramatically reshaping modern understanding of ancient Indian political thought .

While traditionally considered a Hindu Brahmin, recent scholarship based on Jain texts suggests Chanakya may have been Jain by religion . These sources indicate he was born to a devout Jain father and eventually embraced Jain monasticism in his later years . This alternative religious identity challenges popular perceptions and highlights the complex religious landscape of ancient India.

The dramatic timeline discrepancies continue to fuel scholarly debates. The Mudra Rakshasa was written approximately 1,200 years after Chandragupta’s reign, and there remains significant “controversy over the Gupta timeline” . Some historians have even proposed that Chanakya may not have belonged to Chandragupta’s period at all but rather “came at a later date,” with his character “further elevated by contemporary writers by making him the Godfather of Chandragupta Maurya” .

The British colonial era introduced Western historical frameworks that often dismissed Indian historical traditions. As one source notes: “We Indians believe the stories written by Britishers or some others who were not Indians at all, and we don’t believe the stories written by our own Indians” . This epistemological conflict continues to influence how Chanakya is understood and interpreted within academic discourse.

Chanakya’s strategic principles continue to be studied in military academies and political institutions worldwide. His concepts of:

These concepts remain relevant in contemporary international relations and security strategy.

Chanakya’s economic ideas predate and in some cases anticipate concepts associated with classical economics . His works discuss:

Modern economists have noted his contributions to early economic thought, with some recognizing him as “the pioneer economist of the world” .

Corporate leaders worldwide have embraced Chanakya’s teachings on leadership and organizational management. His emphasis on:

These principles have found application in modern business management and leadership development.

Chanakya emerges from the mists of history as a figure of extraordinary complexity—simultaneously a pragmatic strategist and profound philosopher, a ruthless political operator and spiritual seeker, a kingmaker who ultimately renounced power. The contradictions and mysteries surrounding his life only enhance his fascination across centuries.

His enduring legacy lies not merely in the empire he helped build but in the intellectual frameworks he developed for understanding power, governance, and human behavior. The continued relevance of his ideas in fields ranging from political science to management theory testifies to their profound insight into universal principles of organization and strategy.

Perhaps most importantly, Chanakya represents the enduring power of knowledge and intelligence over brute force and inheritance. From humble beginnings—whether his own or those of his protégé Chandragupta—he demonstrated how strategic thinking and determined action can reshape worlds. His life offers timeless lessons about the complex interplay between ethics and effectiveness, means and ends, vision and execution.

As we navigate an increasingly complex global landscape, Chanakya’s multidimensional approach to challenge-solving—incorporating economic, military, diplomatic, and psychological elements—provides valuable insights for addressing contemporary problems. His legacy continues to inspire those who recognize that true power lies not merely in controlling territories but in understanding the fundamental principles that govern human societies.

You know that feeling. Your alarm jolts you awake, and before your eyes are even open, the mental checklist starts scrolling, Laozi : emails to answer, deadlines to meet, groceries to buy, notifications piling up like digital snow. You spend the day pushing, striving, and forcing your way through a world that seems to demand constant, visible effort. Your value feels tied to your productivity. Your peace is a distant country you visit only on vacation, if you’re lucky.

What if we have it all backwards?

What if the secret to a fulfilling life isn’t about adding more—more effort, more control, more hustle—but about subtracting? What if true power isn’t about standing rigid against the storm but about learning how to bend so you never break?

This isn’t a new self-help fad. It’s a 2,500-year-old whisper from the edges of history, from a man who might not have even existed. His name was Laozi (pronounced roughly “Lao-dzuh”), and his tiny book, the Tao Te Ching, is a radical guide to living in harmony with the deepest rhythms of existence. It’s not about doing more. It’s about being more by finally, mercifully, doing less.

Let’s start with the beautiful mystery of it all. “Laozi” isn’t really a name; it’s a title. It means “Old Master” or, even more wonderfully, “The Old Child”. The stories about him feel like parables themselves. He was said to be a lonely archivist in the royal Zhou dynasty library, watching the world outside grow increasingly complex, corrupt, and noisy. Tired of the chaos, he decided to leave civilization behind.

As he rode his ox toward the western mountains, a gatekeeper at the final pass stopped him. This guard, Yin Xi, sensed an immense wisdom in the old man and begged him not to disappear without leaving his knowledge behind. Moved by the request, Laozi sat down and in a single, timeless sitting, wrote a brief text of just 5,000 characters. He handed it over, then passed through the gate and vanished into the mist, never to be seen again.

That text was the Tao Te Ching.

Now, historians will tell you he probably wasn’t one man. He might have been a composite of many wise teachers, or a brilliant literary invention. But that debate misses the point entirely. The fact that we can’t pin him down is the first lesson. Laozi embodies the very idea he taught: that the most profound truths are often hidden, unnamed, and work not through loud force but through quiet, effortless influence. He is the mystery that points to a greater mystery. Chasing the historical facts about him is like trying to catch the wind in a box. You’ll miss the feeling of the breeze on your skin.

So, what did he write in that mysterious text? It begins with a warning and a wink: “The Tao that can be spoken is not the eternal Tao.”

Right away, he tells us, “What I’m about to point to can’t be fully captured in words.” The Tao (pronounced “Dow”) is the core concept. The word itself means “The Way” or “The Path”. But it’s not a path you walk on. It’s the natural order of the universe itself. It’s the rhythm behind everything—the way seasons change, the way rivers flow to the sea, the way a seed knows to become a tree.

Trying to define the Tao is like trying to define “gravity.” You can’t see it, but you can see its effects in an apple falling from a tree. You can’t hold it, but you feel its constant pull.

Our modern minds are trained to analyze, label, and dissect. We see a forest and immediately think “timber,” “ecosystem,” or “hiking destination.” The Taoist approach is to simply experience the forest—to feel its quiet grandeur, to notice the interplay of light and shadow, to understand intuitively that you are not a visitor in it, but a part of it.

This is the shift: from thinking to feeling, from forcing to flowing.

This leads us to Laozi’s most famous and most misunderstood idea: Wu Wei (pronounced “Woo-Way”). It’s often translated as “non-action,” which to our busy ears sounds an awful lot like laziness, apathy, or checking out.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Wu Wei is not inaction. It is right action. It is action that is so perfectly in tune with the flow of the Tao that it becomes effortless, spontaneous, and incredibly effective. It’s the action of the natural world :

In our own lives, Wu Wei is that state of “flow” or being “in the zone” :

It’s the difference between a novice gardener yanking a weed (and breaking the root) and a master gardener who loosens the soil just so, allowing the weed to slide out whole. The result is the same, but the master did it with less effort, less damage, and a deeper understanding of the way things work.

Wu Wei is about working with the current, not against it. It’s the profound understanding that sometimes the most powerful thing you can do is to stop pushing.

Laozi loved paradoxes. He turned our everyday assumptions upside down to help us see a deeper truth. Our world worships the hard, the solid, the rigid: the steel skyscraper, the unyielding opinion, the tough-as-nails leader.

Laozi asks us to watch what happens in a storm. The mighty oak stands rigid and proud against the wind until, with a terrible crack, it snaps. Now, watch the bamboo. It bends low, yielding completely to the wind’s fury. When the storm passes, it springs back, unharmed and rooted more deeply than ever.

He champions the soft, the yielding, the receptive—the feminine principle, or Yin. He doesn’t reject the active, masculine Yang energy, but he begs for balance. In our Yang-obsessed world of constant doing and achieving, we’ve forgotten the incredible power of Yin: receiving, resting, nurturing, and allowing.

True strength, in Laozi’s view, isn’t about dominating others. It’s about the resilience to adapt, to yield, and to endure. The most powerful leader isn’t the one barking orders from the front, but the one who serves from behind, empowering others so much that they say, “We did it ourselves.”

So how do we apply 2,500-year-old wisdom in a world of apps, deadlines, and Zoom calls? Laozi doesn’t hand us step-by-step instructions, but he gives us principles that are timeless.

Even five minutes of mindfulness—observing your breath, noticing the sensations in your body, or simply listening to the ambient sounds around you—can reconnect you to the Tao. This is not a luxury; it’s a vital recalibration. Flow doesn’t appear when you rush; it appears when you pause.

Next time you’re faced with a decision, experiment with Wu Wei. Instead of forcing the outcome, align yourself with the situation’s natural tendencies. Often, the easiest path is also the most effective.

Practice yielding before reacting. Listen more than you speak. Step into someone else’s perspective. Strength isn’t about winning arguments; it’s about creating harmony and resilience, like bamboo bending in the wind.

Remove unnecessary clutter—digital, mental, and material. Being focused, centered, and present often brings more results than a frantic attempt to do everything at once. Simplicity reveals the path more clearly than complexity ever could.

Following Laozi doesn’t require a complete lifestyle overhaul. It’s less about drastic change and more about subtle shifts. The revolution happens quietly inside, as we learn to notice rather than control, to yield rather than dominate, and to let the Tao guide our actions instead of our ego.

Modern life often feels like paddling upstream in a roaring river. Wu Wei invites you to feel the current, notice where it naturally carries you, and use its power rather than fighting it. This doesn’t make you passive—it makes you strategic, wise, and serene.

Imagine waking up tomorrow with this mindset. You approach your work with calm attentiveness. You handle conflicts with gentle patience. You take care of yourself without guilt or obsession. You notice the subtle joys—the taste of your morning tea, the laugh of a child, the dance of sunlight across your floor. You act, but your actions flow. You live, but your life is unforced.

That is the promise of the Tao Te Ching. Not a rigid code, not a strict path, but a whisper: “Flow. Bend. Be. The world does not require your struggle to move; it requires your harmony to matter.”

2,500 years later, Laozi still speaks. And maybe, just maybe, it’s time we finally listened.